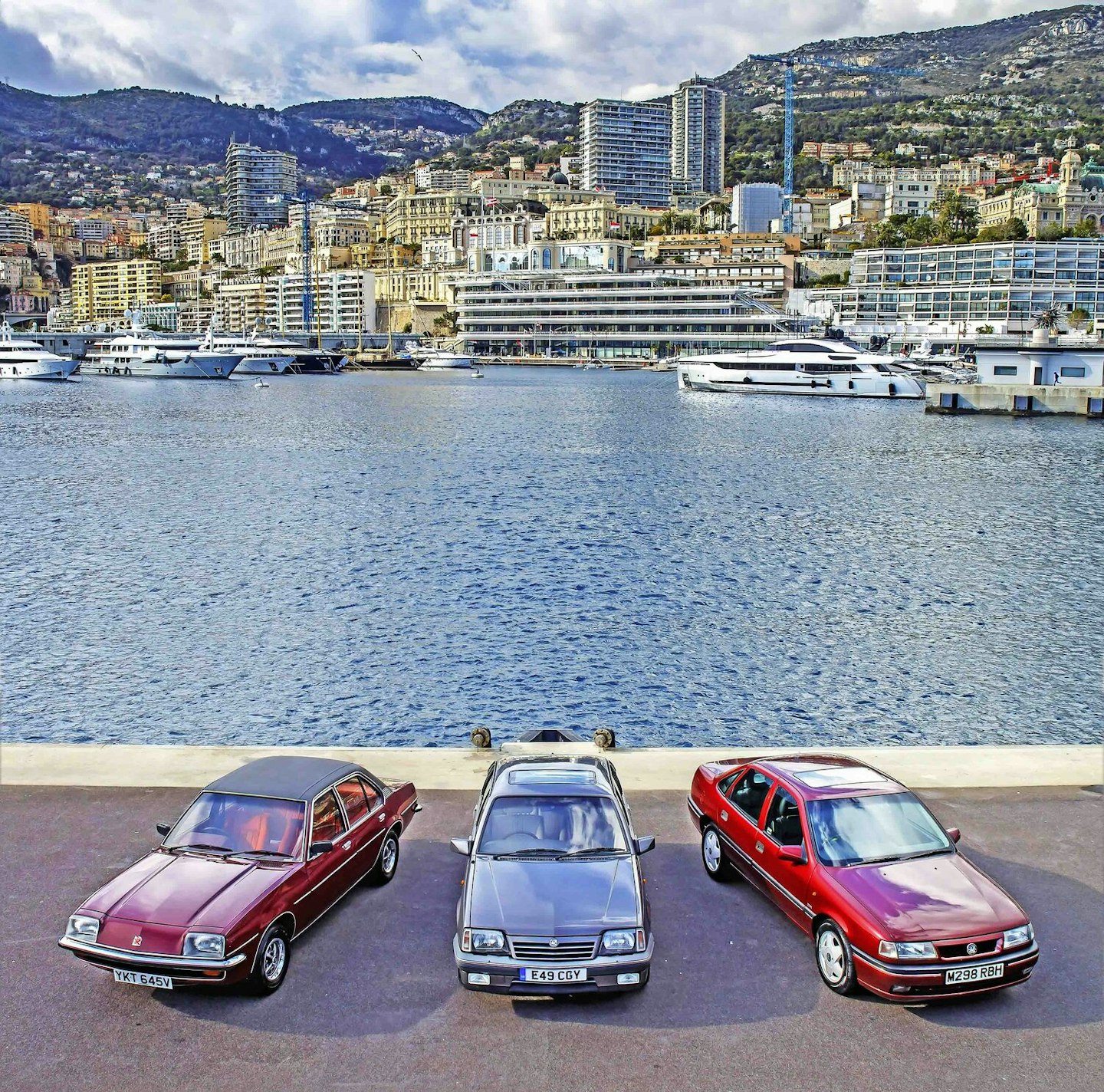

Where have they all gone? How can a model that was once one of the most popular in the UK vanish so completely? The Cavalier was massively important for Vauxhall. It propelled the company into the big league of British sales, and represented the fusion of Vauxhall with Opel, although the coalescence wasn’t entirely smooth. Today it has evolved, via the unloved Vectra, into the Vauxhall Insignia. True, the modern version is no longer made in Luton, but it still bears the Vauxhall griffin badge, even though the Insignia is an Opel in every other market. That griffin is too important a part of the British carscape to lose. There were three Cavaliers, each a temple to GM’s design language of the time – the oldest of the first generation is now 40, and even the youngest of the third generation is 20. Cortinas, Sierras and Mondeos beware…

Cavalier MkI 1975-1981

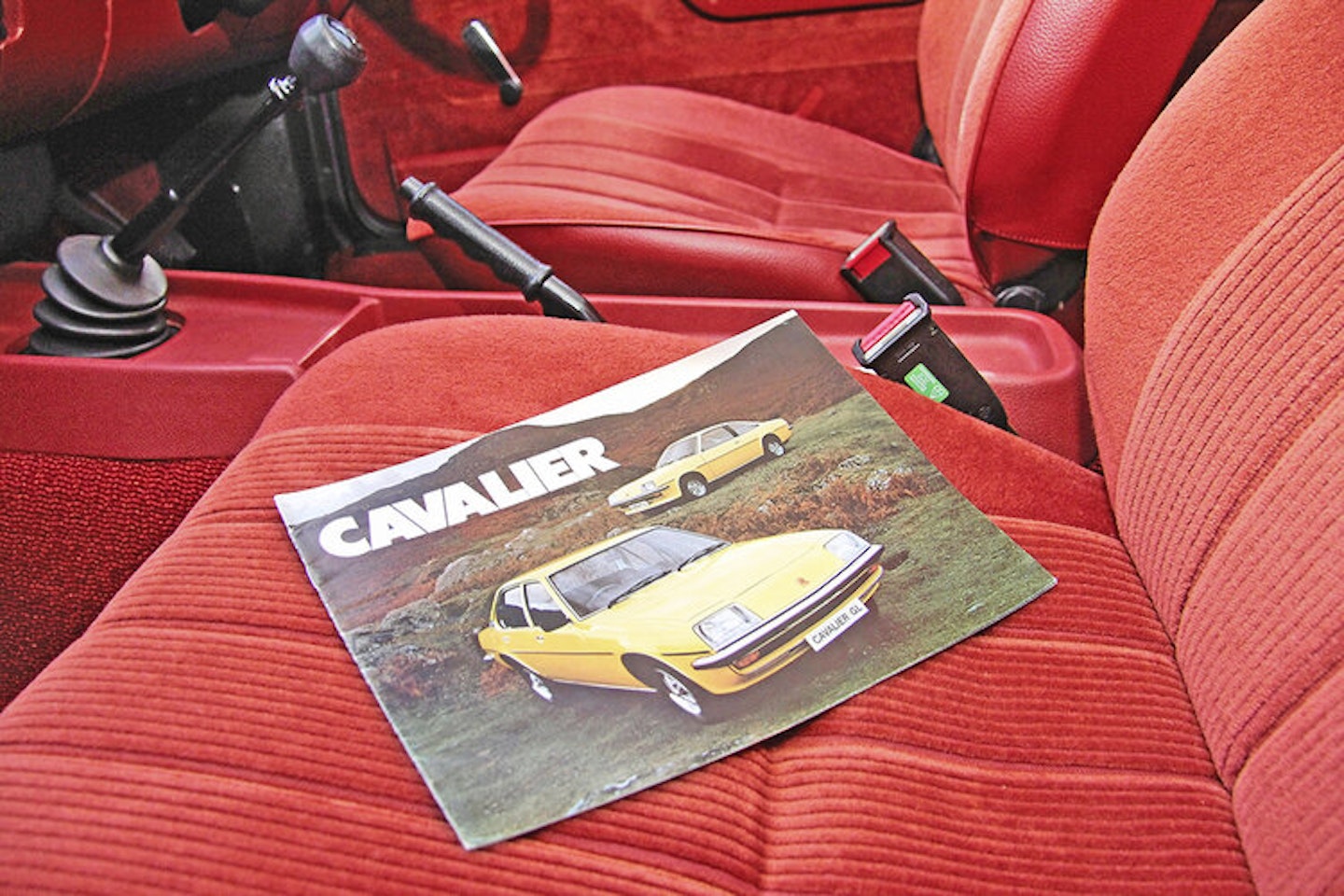

This MkI is a 1980 GLS, the poshest version complete with vinyl roof, Rostyle-like wheels and a very red interior upholstered in the finest velour. The 2-litre Opel engine, cam-in-head but not overhead-cam, generates a healthy 100bhp. And apart from its ‘droop-snoot’ nose, a Vauxhall speciality designed in what remained of Luton’s styling department, this is really a variation of the second-generation Opel Ascona.

Vauxhall was nervous about this in a way it wasn’t with the Chevette, an Anglicised T-car Kadett with a similarly-sloping visage. Maybe it was because, unlike the smaller car, the Cavalier used entirely Opel mechanicals and was initially built in Antwerp, Belgium before production moved to Luton. There was also the curious matter of GM’s internal warfare, with Opels continuing on sale over here even as the Vauxhalls became their near-twins.

Vauxhall needn’t have worried. The Cavalier far outsold the Ascona, and was a rather better driving machine than its Cortina rival in either MkIII or MkIV form. Today it representsa delightful transition between the retro and the modern, with a keen, torquey power delivery able to bridge the gaps between four gear ratios that are long-legged enough for relaxed motorway cruising and selected by a long, languid lever. The three indirect ones whine in an old-school, rear-wheel drive way, unacceptable in a modern world obsessed with refinement, but it is the happy sound of machinery at work.

This Cavalier feels confident, unflustered. Despite keen, beautifully-balanced handling via its front wishbones and live, coil-sprung rear axle it rides with a delightful fluidity lost in its successors. Its brakes are powerful and progressive. The steering feels springy, but that’s just the geometry telling you how the cornering forces are building up and the Cavalier is very easy to place on the road. Those deep windows help here, filling the cabin with light so you can savour the pivoting-penny facia vents, the perforations in the smooth facia’s vinyl to let the loudspeaker’s vibrations escape, and the ample information conveyed by six clear dials under a single sheet of clear plastic.

Our first-generation Cavalier is a handsome machine, roomy, refined and as Anglo-Germanic as its mixed genes suggest it should be. I drove a couple of them when they were new and thought the model delightful. It still is.

Cavalier MkII 1981-1988

This one is a 1987 hatchback in plush CD trim and featuring a three-speed automatic gearbox. It was a bold move on Vauxhall’s part to offer a five-door hatchback as well as a four-door saloon on the MkII’s 1981 launch, and the company must have breathed a sigh of relief when Ford revealed its hatchback Sierra a year later. Now we’re into front-wheel drive via a transverse engine, with strut front suspension and a torsion beam aft. Now, too, the second-generation Cavalier is practically identical to the third-gen Ascona apart from the front grille. But it mattered no longer in the UK because the Opel dealers were gone, most of them transformed into Vauxhall ones. This generation was the really big seller. Praise was piled upon it by the press, pleased to see a British(ish) mainstream family car with a modern mechanical layout. The OHC engine proved a hit, too, be it the baby Family One or the bigger, feistier Family Two. Our car has a 2-litre version of the latter, with a smooth, revvy 113bhp on offer and an instantly recognisable Vauxhall sound suggestive of free breathing and a crisp response.

It’s a facelift model, with wider rear lights and a body-colour front grille with fewer slats (identical to the facelifted Opel one, apart from the badge). It’s fussier-looking than the MkI and less handsome with its ridged-plastic midriff and clumsy sill covers, and those spoked alloys shout affluence rather than aesthetics. Being a CD it’s a temple to silver-grey velour, but it wears its top-model status uneasily with the electric window switches placed as an afterthought behind the gear selector. There are strange angles here, too: the bent handbrake lever, the downward droop of the facia’s cliff-like central stack as it faces towards the driver, a steering wheel whose pivot for the height adjustment (made by Saginaw, whose host town was immortalised in Simon & Garfunkel’s America) is so near that the rake alters alarmingly. However the heating and ventilation controls are an exercise in variable versatility never bettered, and the winding handle beneath the driver’s seat to adjust its height works well.

The engine copes with the three-speed slushmatic admirably, and the CD’s gently-powered steering makes for effortless progress. But I remember this Cavalier generation being short of front-end grip, and suffering from a shudder over bumps caused by the engine bouncing on its mountings. Both characteristics are authentically present in our CD, but nowadays they bring on nostalgia more than irritation. The MkII Cavalier was never a perfect car, but three decades on it’s a surprisingly charming one.

Cavalier MkIII 1988-1995

Underneath, little had changed. Yet on top, all was smoothly new. The rounded yet taut lines and the confident neatness and restraint of detailing surely marked, along with the cute but assertive Corsa of 1993, Vauxhall/Opel’s peak of design. The Cavalier MkIII, launched in 1988 and represented here by a facelifted V6 saloon model from 1995, right at the end of production, is a great-looking car.

Its Opel cousin was now called Vectra, as would be this Cavalier’s less-handsome replacement, but the British interpretation continued to storm the sales charts. Its interior is as attractive as its exterior, with the same basic layout as the MkII’s but much more smoothly and neatly arranged.Here, though, we’ve lost the Saginaw tilt steering wheel for this facelifted model, gaining instead a US-spec ‘full size’ airbag which takes up most of the wheel. This was designed to offer enough of a cushion to protect even an unbelted occupant, even though there was no need. Here, too, is a passenger airbag, usurping the former open facia shelf, and this CDX-trimmed example has luxurious leather trim in black.

As with the MkII, the facelift also brought wider rear lights and a body-colour grille. There was clearly a well-used formula for maintaining a model’s mid-life appeal. This V6 version, designed to push the Cavalier upmarket and snare buyers down-speccing from more extravagant cars, arrived in 1993 with a brand new, 2.5-litre engine sporting 24 valves and a curious 54-degree vee-angle. Power was 168bhp, with some of it spirited away into slush by this car’s four-speed automatic gearbox.

So it’s very smooth and quiet, and the V6’s revised engine mounts have rid it of that Cavalier shudder to bring on a recognisably modern dynamic demeanour. Except that it’s gutless, barely maintaining 70mph on a motorway incline unless you force a kickdown into third gear or press the Sport button to keep fourth gear at bay. Only then does it undergo a dramatic personality change to reveal the rocketship beneath.

Again, I remember that this is how they were; I briefly ran a long-term test Calibra with this powertrain for Carweek magazine, and found it very frustrating. The manual, by contrast, was a discreet hotrod, and would make a fine sleeper classic today.

Who’s coming home with me?

What makes a car into a classic rather than an unwanted has-been can often depend on the old-car-loving public’s interest as much as a car’s innate merit.

And I fear that Vauxhall’s three generations of Cavalier have either missed, or will miss, their chances of surviving long enough to snare keen buyers anew. By the time we remember what we had, they’ll be gone. Even the SRis and the Turbos.

That’s why it was a genuine treat to drive all three of three such survivors. But for me, the revelation of the Cavalier bunch is the handsome, capable and highly characterful MkI. You drive it, and it’s as if the intervening years just never happened. You could use it every day and want for nothing more. There are very few MkI Cavaliers left on British roads now. Buy one while you can.