Words: Andrew Roberts Pictures: Matt Howell

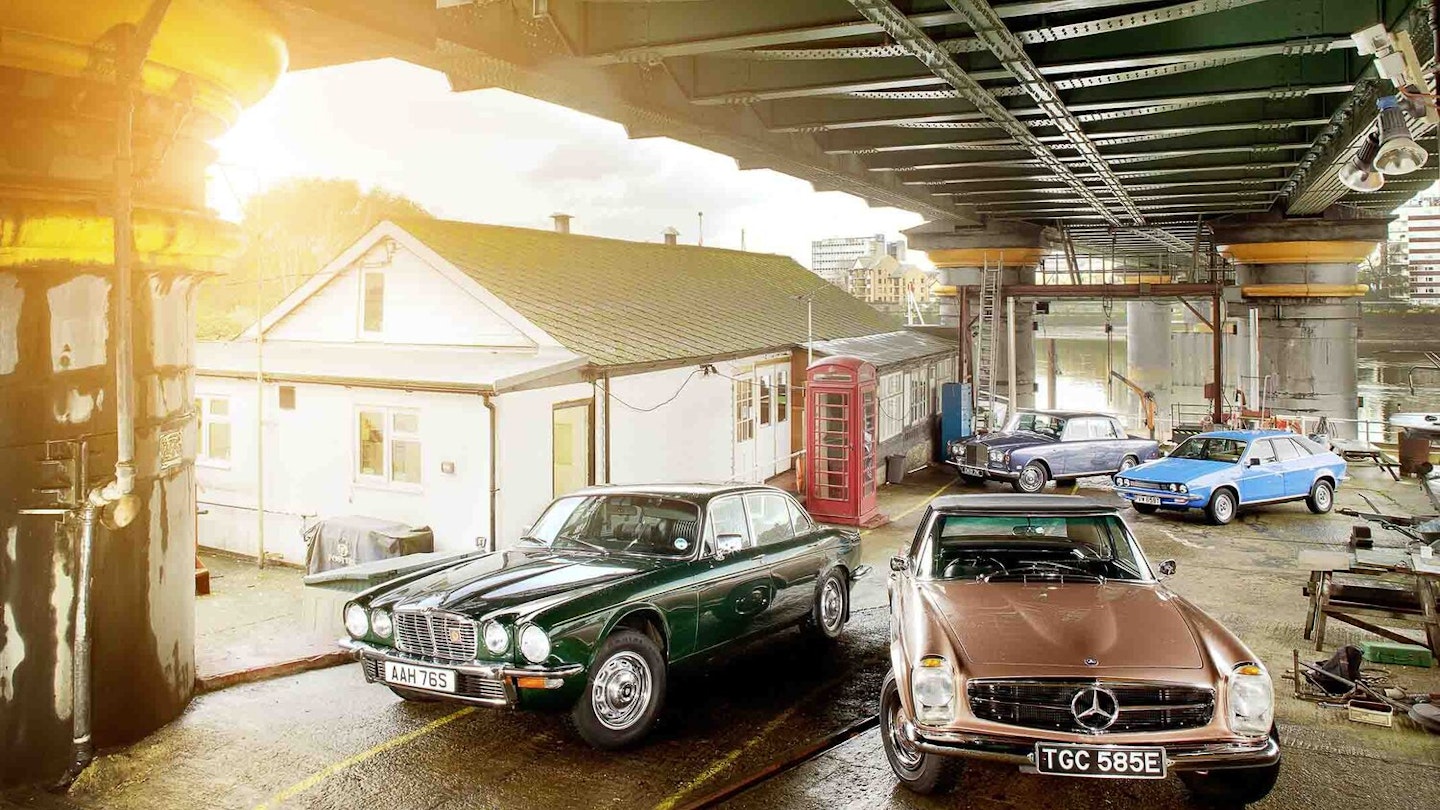

The Long Good Friday is arguably the last entry in the small and select cycle of ‘Great British Gangster Films with Fine Motor Cars’ – namely a Rolls-Royce Silver Shadow S1, property of one Harold Shand. What better form of transportation for a visiting New York Mafia don who’ll hopefully fund Harold’s plans to buy the moribund London docks and redevelop them for the 1988 Olympics. Surely nothing could go wrong – apart from the IRA encroaching on his manor that is. And so we pay tribute to a classic of British cinema and to the talents of one of its finest character actors.

Rolls-Royce Silver Shadow

“Ladies and gentlemen. I’m not a politician; I’m a businessman with a sense of history. I’m also a Londoner.”

When the film entered production, the Silver Shadow had been made for fourteen years and was almost a cliché in some respects. Older Practical Classics readers may remember how virtually every successful TV comedian, entertainer or rock star that couldn’t wait to sell out to ‘The Establishment’ posed for pictures with their new Rolls-Royce. And this is the case with Harold, who looks to be in his mid-forties and presumably began his career nailing rival mobsters heads to Vauxhall PA Crestas and menacing the local Teddy Boys. Now he is on the verge of becoming a ‘legitimate businessman’ and the Silver Shadow is essential to Harold’s ego.

As our test car travels the mean streets of Putney, it still has the power to effortlessly insulate you from the mundane cares of the outside world, without meeting the fate of the unfortunate Rolls-Royce in the film (actually a second example, note the change of upholstery) – not to mention Eric the Chauffeur. Fifty years after the first Silver Shadow was formally launched, JP Blatchley’s design now looks as timeless as his lines for the preceding Silver Cloud. Mr. Shand is clearly an ‘entrepreneur’ of taste, even he is prone to such sayings regarding his disapproval of sub-par American lawyers.

Austin Princess

“Bent law can be tolerated for as long as they're lubricating, but you have become definitely parched.”

Shand has several public officials in his pocket and none more repugnant than Detective Inspector Parky, as played by the brilliant character actor Dave King. His squad car is an unmarked Princess 1700HL Series 2 for The Long Good Friday, making a vehicle then associated with Terry Scott living in fear of Reginald Marsh coming for dinner seem faintly menacing, a symbol of his tainted professionalism.

The second generation Princess range was launched in 1978, replacing the 1.8-litre B series engine with 1.7 and 2-litre O series units. Our test car has all of the charms that make you realise why you might have chosen it instead of a Vauxhall Carlton – it is rather well appointed and the Wedge-shaped lines now seem svelte rather than naff. The O-series engine is not overly smooth and the four-cylinder Princess is not exactly brisk, but the amount of passenger space that is available is remarkable given the modest dimensions. The back seat of the 1700HL is more comfortable than the Jaguar’s and the ride more refined than many more expensive cars. This well preserved Princess is a reminder of the great potential that BL managed to ignore – now that would have made Harold irate.

Enjoying the read? Why not buy a full issue of Practical Classics magazine! Because nothing beats paper right?

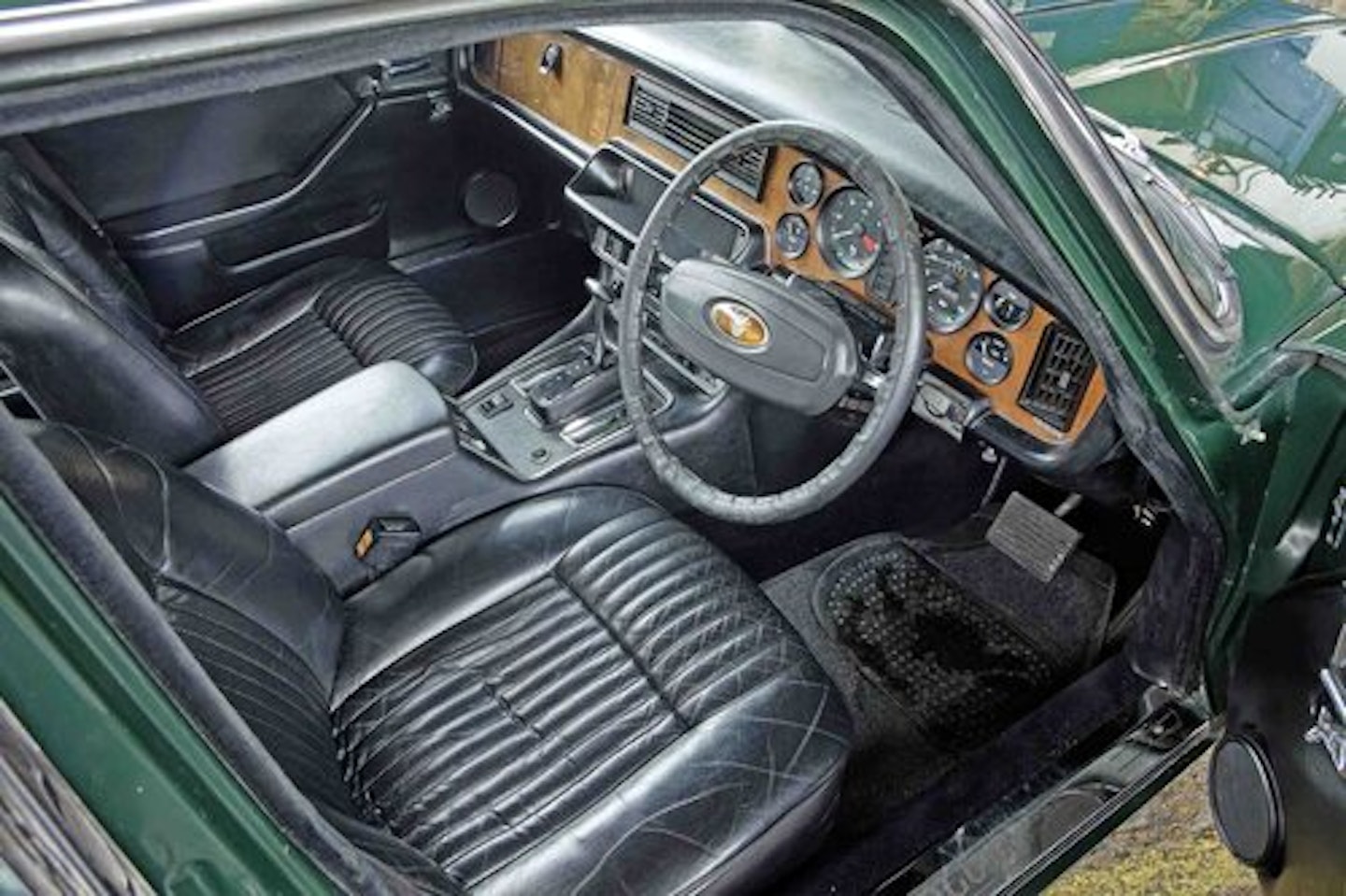

Jaguar XJ6

“Nothing unusual," he says! Eric's been blown to smithereens, Colin's been carved up, and I've got a bomb in me casino, and you say nothing unusual?”

Harold’s two principal forms of transport both appeal to his patriotism, but if the Rolls-Royce reflects his flamboyant side – the hood as showman – his Jaguar XJ6 S2 4.2 LWB is his transport as sober-minded property developer. After he is left with an interesting insurance claim for the Silver Shadow, the Jaguar becomes his main set of wheels, the ideal car to take for a drive up West every so often.

Today, the XJ Series 2 Jaguar is a classic that is all too often taken for granted and our handsome test car is a beautiful British Racing Green reminder (the car in the film was blue, but we think Harold would have approved of BRG) of its greatness. The XJ6’s coachwork is as impressive as the MkX without its excessive width and the Series 2 facelift of 1973 accentuates its elegant front with the smaller grille and raised bumper (to comply with US safety regulations) and the long wheelbase option, introduced in 1972, makes the Jaguar seem even more impressive. Then there is that ever-svelte XK series engine and small touches such as a dashboard as charming but more logically arranged than on the Series 1.

And this XJ6, parked discreetly but menacingly on the banks of the Thames, is all the more an incredible an achievement when you bear in mind that it was made at a time of industrial strife within British Leyland. What Harold thought of Red Robbo is not on record, but it is probably unprintable, and by the late Seventies the Browns Lane factory was emerging from years of underfunding with cars being built on archaic machinery. But this XJ6 4.2 looks potent even in repose, a car that is at home in the docklands as it is sweeping up outside of the Savoy Grill.

It is in the Jaguar when the IRA, in the person of a very young Pierce Brosnan, finally captures Harold – the film’s John Mackenzie did not want to ‘go for conventional ideas of what IRA guys are like.’ When the last scene was shot the XJ6, driven by Mackenzie himself, left the Savoy and turned left into the Strand before heading towards Trafalgar Square. And there, on the back seat of the Jaguar, Francis Monkman’s theme music accompanies Bob Hoskins giving a master class in screen acting equal to any in cinema.

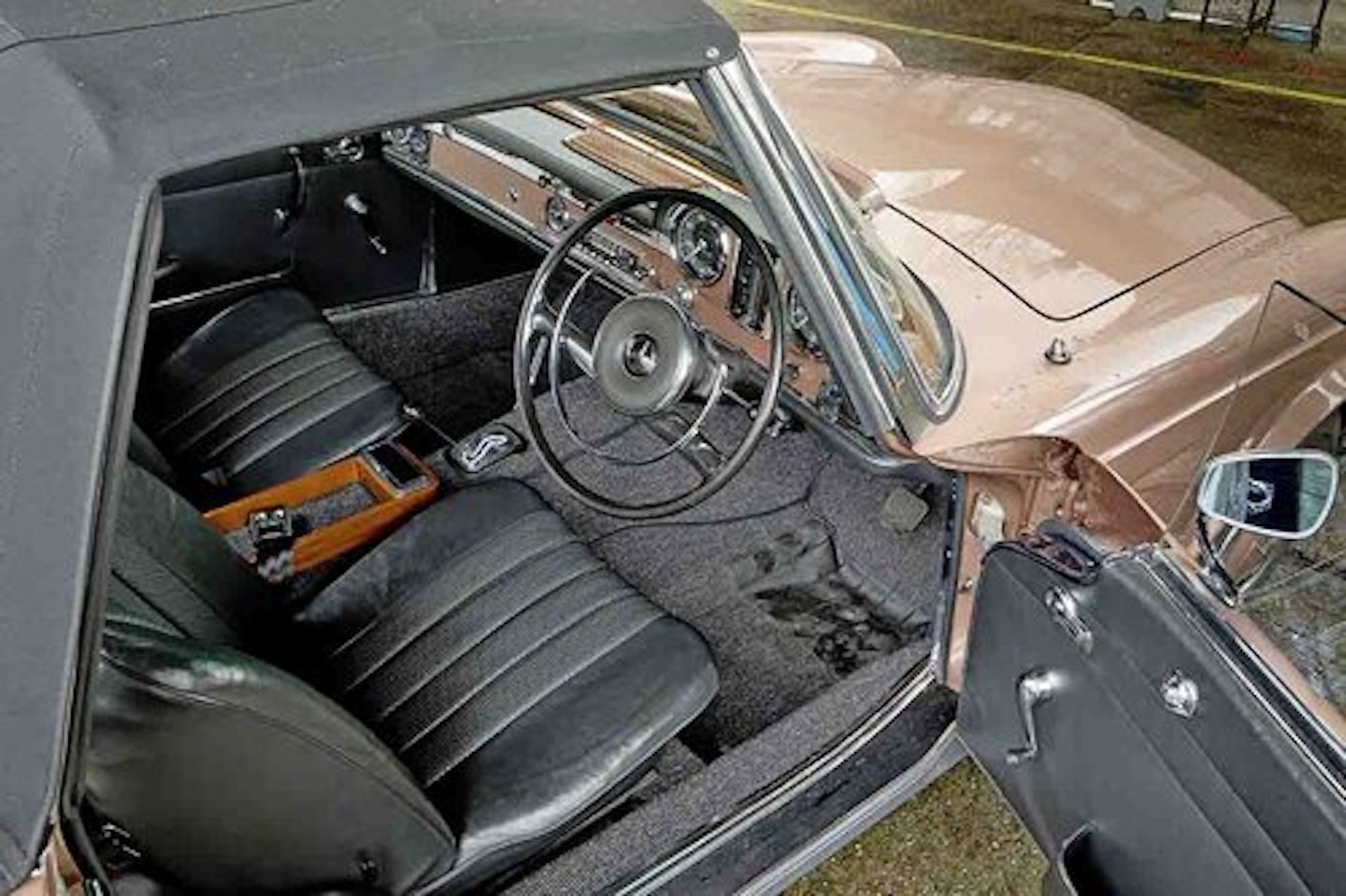

Mercedes-Benz 280SL

“What I'm looking for is someone who can contribute to what England has given to the world: culture, sophistication, genius. A little bit more than an 'ot dog, know what I mean?”

In a lesser film, Harold’s acolytes would have likely used Mercury Monarch Ghias and gold digital watches to display their ill-gotten wealth, but The Long Good Friday used the Pagoda. When shooting commenced, the most recent example was already eight years old but a Mercedes-Benz ‘Pagoda’ 280SL bespoke good taste, a continental outlook and the very wise decision not to outshine any car owned by Mr. Shand. To do otherwise might see concrete boots and the River Thames featuring in your immediate future.

The W113 series Mercedes-Benz was launched as the 230SL in 1963, the ‘Pagoda’ name deriving from its slightly concave hardtop. Our example, adding notes of Continental sophistication that would have appealed to Harold’s sense of upward mobility, is a prime example of the 250SL, the most exclusive of the entire range. It was launched in 1967 as an interim model before the debut of the 2.8-litre 280 and only 5196 were ever made. Power was now from a 2.5-litre straight six and although a 5-speed manual box was available, it was rarely specified, as a 4-speed automatic transmission was the norm. Every SL came with a detachable roof as standard – essential for keeping your suit smart when waiting for your boss outside of a casino on a rainy night.

And any London hood’s henchperson who preferred the Pagoda to a Canadian import ‘Yank Tank’ showed remarkably good tastes, as the 250SL is, frankly, a gem. Every detail, from the lines to the functionally elegant dashboard is virtually perfect and whilst the metallic paint finish, the stacked headlamps and that vast red steering wheel inform any passer-by that here is a very expensive motor car the Pagoda is certainly not for Flash Harries. The suspension design and the wide track combined with that power plant doesn’t just make for an elegant cruiser befitting Audrey Hepburn (you can imagine Harold relaxing with Two for the Road after a hard night’s knee capping) but a true sports car.

In fact the only aspect of using a 250SL to escape the law that might cause slight problems is the fact that the gate of the automatic ‘box is the reverse of standard practice. It is a car of understated and very real distinction and its high price reflects its unfailing pursuit of engineering excellence. ‘We're in the Common Market now, and my new deal is with Europe!’

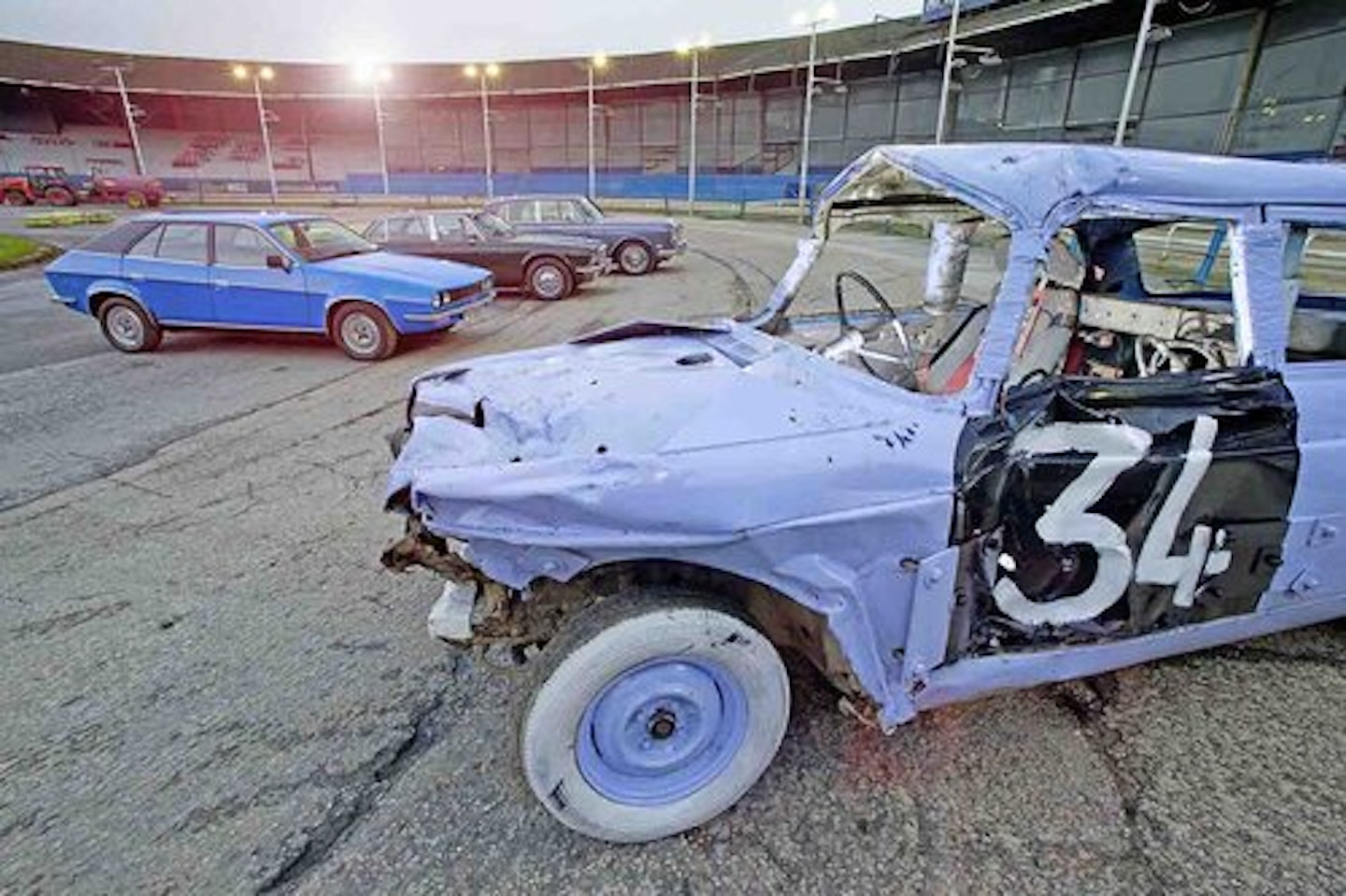

Morris Oxford

There's a lot of dignity in that, isn't there? Going out like a raspberry ripple.”

Whatever views you may hold on the subject of banger racing, it is an aspect of a film that uses the sights and sounds of a real 1979 vintage London. Even by the standards of 36 years ago, a budget of £1million was minimal and this meant that John Mackenzie was obliged to shoot over fifty per cent of feature on location. In the Harringay stadium you can almost smell the hot dogs and the engine oil when Harold, not in the best of moods, has a hitman blast two IRA activists who he suspects of planning his downfall with a shotgun. He also disposes of Harris, a now surplus to requirements county councillor on the Shand payroll.

One of the drivers was John King who recalls ‘the banger scene being shot on two nights. My car is the purple checked Farina you see on screen and that was shot on a Saturday night. Cambridges and Oxfords were popular because they were cheap and tough and it was not uncommon to fit MGB engines to get the best performance out of them.’ After the regular meeting ended at 10.30pm, the crowd was invited to remain to watch the filming take place – ‘shooting started so late for me that they had to wake me up!’

The corpses crash through a plate-glass window – according to John ‘that box was specially constructed for the film’ – causing a salmon pink coloured Austin A60 Cambridge (no. 679) to somersault and overturn. So, at Wimbledon Stadium – Harringay closed 28 years ago – Jerry Ansell has paid tribute to the film by spraying his Morris Oxford in Long Good Friday colours. We also asked for volunteers for the ‘corpse on the circuit’ scene, but no one seemed keen…

In the 1970s the pastime was generally known as stock car racing (road cars with added protection for close contact) and was screened every Saturday on ITV’s World of Sport. Bill Maynard even recorded the song Stock Car Racing is Magic – one dire enough for Shand to use on recalcitrant business rivals. John King earned ‘£50 for my brief moments on the screen’ and the film does capture some of the ‘amazing atmosphere we used to have at Haringey.’ And the scene also has an ominous subtext for Harold – he may have thought of luring local IRA members to the track with money only to have them killed, but like the BMC relics hurtling around the track, he is another 1960s survivor who is doomed.

Conclusion

“The days when Yanks could come over here and buy up Nelson's Column, a Harley Street surgeon and a couple of windmill girls are definitely over!”

This is emphatically not a film celebrating a barrel full of mockney monkeys. The Long Good Friday shows a London where surface glamour and chefs serving ‘poncy French food’ is underpinned by a network of corrupt local councillors and seedy police Inspectors. And yet, the city that Harold hopes to transform seems so semi-derelict, and Hoskins’ performance is so dynamic that you half hope that Shand will succeed, despite his motors, his yacht and his entire way of life being built on the misery of others. ‘We’ve got mile after mile, acre after acre of land for our future prosperity… so it’s important that the right people mastermind the new London…’