Prototypes that never made it into production are enigmas of the automotive world. Some could have made a dramatic impact on their manufacturers’ fortunes and even on automotive history. The line-up here brings together five such unrealised stars. There’s the Triumph TR7 Lynx and Rover P6BS from the Heritage Motor Centre collection and a trio of experimental cars in the Zagato Zimp, Berkeley Coupé and Mini Beach Car which are now owned by intrepid enthusiasts. So let your imagination take you back to the times when these cars were created and ask yourself ‘What if…?’

ZAGATO ZIMP

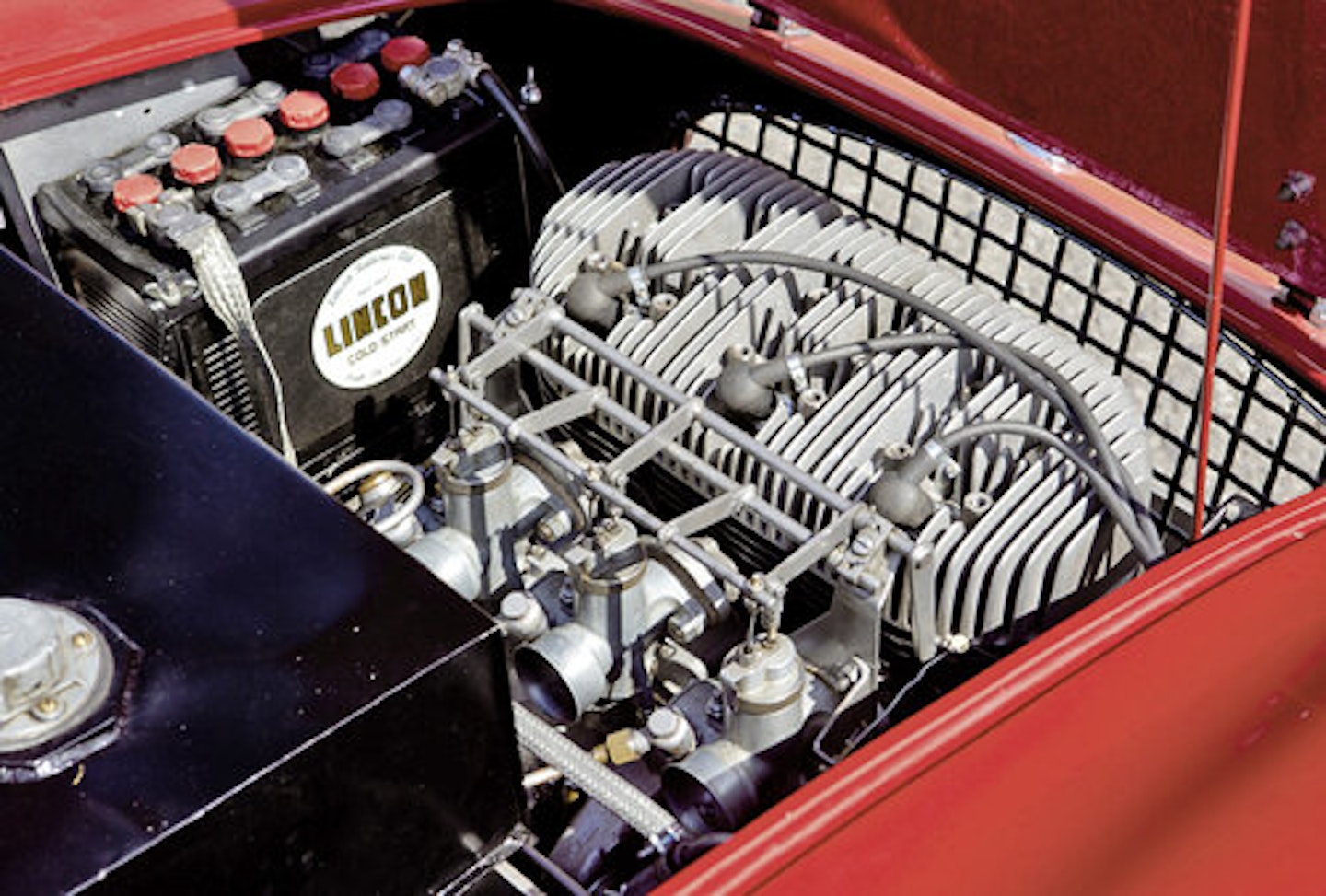

At first sight, the Zagato Zimp looks very Continental, elegant and expensive, from its wooden steering wheel to the impeccably minimalist lines of its aluminium coachwork. Then you notice its instrument panel and hubcaps are more Linwood than Italy, and that familiarity is confirmed when turning the ignition key which produces the Coventry Climax engine note known and loved by all Hillman Imp owners.

In 1963 Zagato of Milan saw the potential of Rootes’ new small car as the basis of a small British-built four-seater coupé that would avoid the swingeing UK import duties imposed on foreign-built cars until 1973. The plan was that cars would be constructed by British Zagato Ltd, a new company founded by businessmen Anthony Charles and Peter Thomas on the basis of a verbal undertaking from Lord Rootes that they would receive the supply of Imps vital to their enterprise.

Zagato was already working on a right-hand drive Imp it had acquired secondhand, and this was joined by two more bought by Peter Thomas from an Oxfordshire dealer and driven to Italy by him and his wife. After nine months of intensive work, the three Zimps – two red, one white – were ready for display at the 1964 Earls Court Motor Show. However, 1964 was also the year Chrysler took a share in Rootes and, in the words of Imp expert Mike Hanna, ‘When the Chrysler rep saw the Zimp, that was it.’ The project was binned. All three cars survive today, two of them owned by Mike.

His white Zagato was driven for years by Peter Thomas, who then sold it to Anthony Charles before Mike acquired the car in 1986 in much the same state as you see it now. From a 2015 perspective, it’s a stunningly graceful coupé with styling by Ercole Spada, the man who crafted the Aston Martin DB4.

The flexible engine and sure-footed handling of the Imp saloon put the Zimp in the Mini Cooper class. Aluminium construction means the Zimp is also 200lb lighter than its parent model.

The Zimp is a car that raises questions and provokes debate. It would almost certainly have been more expensive to build than Rootes’ own 1967 Sunbeam Stiletto – Rootes’ Ryton factory evaluated the car and said build costs were unlikely to be less than £1000, which was more than a Mini Cooper S. But, as Mike points out, the Zimp was aimed at the ‘executive’s wife’ market, so it’s probably fairer to view it as the UK equivalent to the Lancia Fulvia Coupe.

Small Car magazine tested Mike’s red Zimp in January 1965. It felt it would appeal to ‘drivers who can afford to pay more for elegance and style’ and that the Zimp deserved to succeed. The idea of a chic Zagato-bodied coupé still beguiles today.

BERKELEY COUPÉ

Between 1956 and 1960 the Berkeley Coachworks Factory at Biggleswade, owned by the caravan maker Charles Panter, produced a range of innovative glassfibre-bodied light cars that were just right for hill-climbing or nipping down to Brighton.

Berkeley’s sports cars are generally associated with open-top motoring, but the car here is believed to be the factory’s hard-top prototype. It came to light in 2010 when a man in Chesham was clearing out his late father’s estate. Graham Higgs, of the Berkeley Car Club, was intrigued enough to travel to view the car and found that when the Berkeley factory closed in 1961, the garage’s owner had bought ‘a good many spares’ plus a bodyshell.

Graham inspected the door assembly and realised this was a works car, not an aftermarket hardtop conversion. He bought the shell and his research led him to the conclusion that this was the one and only factory-built Berkeley hardtop. ‘It was probably developed as a twin-cylinder car in 1956 and was then fitted with the 492cc Excelsior three-cylinder engine,’ he says.

Photos taken in 1957 indicate the car was displayed at the Earls Court Motor Show, but by the end of that year Charles Panter had cancelled the project. One possible reason was cost and another, as Graham tactfully points out, was the tiny car’s potential for claustrophobia. The coupé remained at the plant as a development mule and was photographed in the company of Berkeley rally cars at Heston Airfield. When Graham bought the car it was a bodyshell with rear suspension, but no glass or engine. After two years of hard work its condition was as you see it here. It looks appealing, but could never be described as spacious and, despite being the only Berkeley to feature an external door handle, it offers as much luxury as a go-kart. However, firing the engine via the Dynastart system is a unique experience as the Coupé sounds like a Qualcast lawnmower primed for Formula One.

And, as any Berkeley owner will tell you, sitting only four inches above the tarmac and with the engine buzzing wildly, 30mph feels like 100mph. Whether the Coupe could have staved off Berkeley’s demise is an intriguing question. The advent of the Austin-Healey Sprite in 1958 severely affected manufacturers of small sports cars and a hardtop version of the Berkeley may not have greatly expanded its appeal. But this well-proportioned coupe does illustrate the scale of ambition at the Biggleswade factory – and how many other sports cars can achieve the heights of such jauntiness?

AUSTIN MINI BEACH CAR

How you react to the Mini Beach Car depends on your location and the weather. It’s the perfect transport to whisk you to a beach bar in sun-drenched Jamaica, but under a grey West Midlands sky you may question why on earth you would want a Mini with no heater and no doors – though Mini designer Alec Issigonis was said to have liked the Beach Car a lot, possibly because it fitted with his individual notion of uncomfortable transport.

None of this means that the Beach Car isn’t fun – on the contrary, it has all the dynamism and pep of a 1962 Austin Mini, only with the added benefit of all the natural air conditioning you could want. Getting in and out couldn’t be easier (there are not terribly reassuring chains to prevent unscheduled exits) and the wickerwork seating is at least more comfortable than the early Mini Moke, reinforcing the view that this is a car primarily intended for short journeys in hot weather.

Intended to rival Fiat’s 600 Jolly as transport for upmarket hotels, the Beach Car was developed at Longbridge’s Experimental Department under the supervision of BMC chief stylist Dick Burzi. The Mini’s side panels were removed and the spot-welded roof was supported only by A and C pillars. One prototype – recently discovered in Greece – was based on a Wolseley Hornet, but all the other 13 Beach Cars made between December 1961 and March 1962 were based on the standard Austin Mini. Most went to the USA where dealers used them to promote the Mini’s debut on the American market, and the car here is the only right-hand drive example. It was famously lent to the Royal Family, so this is no ordinary doorless Mini – it’s a doorless Mini that might have been driven by Her Majesty The Queen.

With the introduction of the Mini Moke in 1964, BMC had a new offering for the hotel/resort market and it’s difficult to see how the Moke and Beach Car could have successfully competed for the same customers. By 1968 the British-market beach car had returned to Longbridge and was in danger of being scrapped until Bob Hart’s intervention. Bob had joined Austin as an apprentice in 1965 and, after hearing of plans to rid the factory of unwanted projects, the Hart family became the proud owners 47 years ago of the only (officially) doorless Mini saloon in the UK. ‘The open sides never bothered me because I rode a motorcycle at the time,’ he explains.

Bob doubts whether the Beach Car stood a real chance of entering full-scale production – ‘the cost of the tooling would have been heavy and BMC never liked to spend money so I doubt whether it could ever have made a profit’ – but his car is a testament to a glorious period of innovation at BMC, a time when the Mini’s potential seemed limitless. Wickerwork upholstery notwithstanding.

TRIUMPH TR7 LYNX

At first sight the Lynx looks as though the designers of the nose and tail – Harris Mann and Solihull’s design studio respectively – were not on speaking terms. During the development stage David Bache was instrumental in losing the TR7’s swage lines and the result is a coupé whose lithe profile eventually grows on you. It’s also rather well-planned; the wheelbase is around 11 inces longer than the TR7 and its larger doors help to balance the lines and allow easier access to the folding rear seats.

The origins of the Lynx date as far back as the late 1960s when Triumph was considering a four-seater coupé powered by the marque’s 2.5-litre straight-six. By 1972 rumours of impending legislation banning open cars in the USA – the market that took 80 per cent of British Leyland’s sports models – prompted Triumph to plan both the TR7 and the Lynx, a three-door hatchback version. To save costs, the Lynx’s five-speed gearbox, rear axle and engine would be from the Rover SD1, which was still under development. Power would come from the familiar 3.5 V8 rather than the problematic Stag three-litre engine.

The Lynx was due to be built alongside the TR7 at Triumph’s Speke works on Merseyside and tooling was put in place for annual production of around 19,000 cars. Then in 1978 new British Leyland chairman Sir Michael Edwardes announced that after years of industrial turmoil Speke was to close. TR7 construction was switched to Canley and the Lynx project found itself unexpectedly canned.

One issue preventing the Lynx entering production was that its parent TR7 was not popular in the USA. The Lynx’s chances there may have been even more limited, although Bob Hart, our Mini Beach Car owner who actually worked on the Lynx, believes it was killed off for political reasons. ‘There were some problems with the electrics,’ he says, ‘but the main reason was that it was an upmarket hatchback with a V8 engine and that would have clashed with the Rover SD1.’

Perhaps the Lynx should be regarded not as a sports car but as a GT successor to the Stag and an alternative to the roomy ‘liftback’ Ford Capri 3000 Ghia and Reliant Scimitar GTE. Its cabin is typical 1970s British Leyland with lashings of black plastic and would have needed significant improving, along with the standard equipment spec, to tempt US customers away from their superior Mustangs. And, by replacing the long-throw manual transmission with an automatic box, Triumph might have even got itself a 280ZX rival. But all these modifications would have taken time and planning – quite clearly something British Leyland didn’t have.

ROVER P6BS

The P6BS gives us a tantalising glimpse of a parallel universe where Rover produced a range of successful upmarket cars to rival Mercedes-Benz, BMW and Audi. The tragedy is that there seemed to be no reason to doubt this vision of the future when Rover displayed its mid-engine sports car at the 1968 New York International Automobile Show. In the mid-1960s, following the success of the Rover-BRM sports car, Rover launched a mid-engined sports car project powered by the 3.5-litre V8 recently acquired from Buick.

eams working at Solihull and the Alvis plant in Coventry (part of Rover since 1965) put a Vauxhall Viva steering rack and P6 rear suspension into aggressively functional bodywork devised by Rover engineers. It also has a Spen King-designed free-flow exhaust system, while a Perspex dome covered twin SU carburettors. The engine is possibly a Buick unit, rather than one made by Rover, and gives 35bhp more than the familiar P5B unit. It’s also offset 5½in to the right to accommodate the Alvis-devised transmission.

One challenge facing mid-engine coupé designers was how to combine the advantages of traction and light steering with practical accommodation, and here King was entirely successful. Inside, the P6BS combines E-type seating plus a seat for a sideways-facing rear passenger. This is a coupé capable of 140mph that’s also very easy to enter, with plenty of legroom for tall drivers because the engine layout provides very deep footwells.

The careful detailing, from the standard of trim to a dashboard that anticipates the Rover P6B saloon by several years, displays how serious Rover was about its project. In short, the P6BS was a car with the potential to compete with Ferrari and the E-type, especially as the intended price was a mere £1500. Success looked to be even more assured when David Bache restyled the coupe as the P9, a svelte and elegant offering that was intended to bear Alvis badges. However, the formation of the British Leyland Motor Corporation in 1967 meant Rover and Jaguar were part of the same industrial giant – and the latter ensured that Rover’s mid-engine supercar never entered production.

And this is a real tragedy, for although the P9 may have been a niche offering and probably wouldn’t have worn a Viking badge, it would still have reflected well on Rover. The PB6S/P9 could have been the flagship of a range of cars globally admired and backed by the might of what was then Europe’s largest car company. ‘The finished product really could be a world-beater,’ enthused Motor magazine in March 1968 – and rarely in automotive history has the word ‘could’ been so emotionally weighted.